All eyes in the fight over reproductive rights and justice have been focused on a federal judge in Amarillo, Texas. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk will soon decide a case involving the first drug in a medication abortion, mifepristone. Though the case makes wholly unpersuasive arguments, undermined by the facts and the evidence, plaintiffs filed in this specific court because Kacsmaryk is one of the most conservative judges on the federal bench and has an explicit and documented animus toward abortion. The expectation is that he will do everything in his power to end medication abortion as we know it. Because states like Texas have already banned abortion (including medication abortion), the deep fear is that his ruling could affect abortion care even in states where it remains legal.

But we would like to offer some clarification here. Because despite the barrage of predictions that this case could ban mifepristone and take it off the market, there are several basic legal principles suggesting that Judge Kacsmaryk’s power is limited and that a ruling for the plaintiffs will not necessarily change much at all with medication abortion.

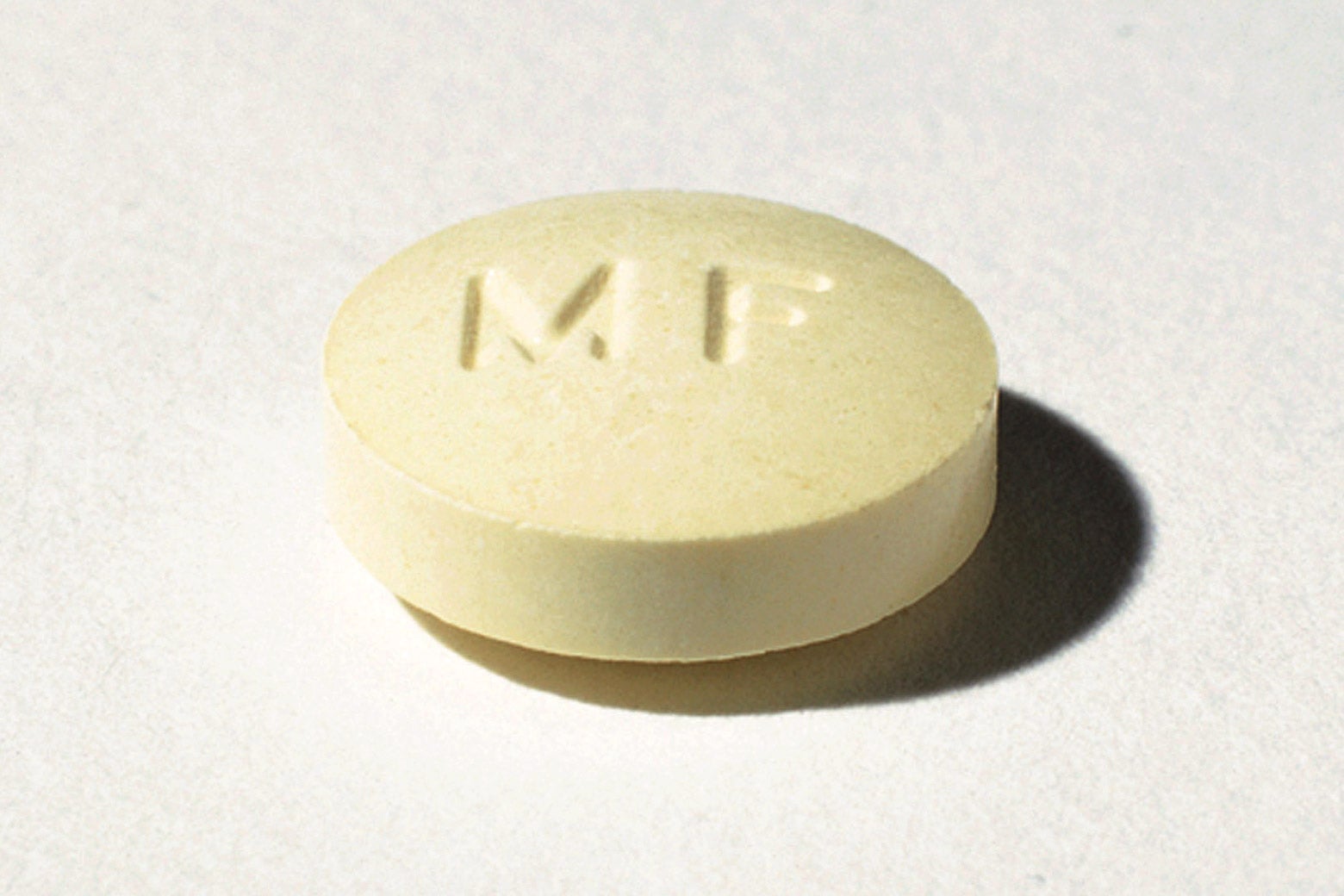

Some background first. Medication abortion typically occurs, in this country, with two different drugs—mifepristone followed by misoprostol. From the most recent data, abortion pills account for roughly 53 percent of abortions in this country, and given that this data is a few years old now, it’s probably much higher. Many people prefer medication abortion for a variety of reasons: It allows people to have an abortion in the privacy of their homes and it is available by telehealth, which is usually cheaper than an abortion at a brick-and-mortar clinic.

Because of the increasing importance of medication abortion in the face of all of the restrictions and bans following the Dobbs decision, an anti-abortion group filed this lawsuit challenging the Food and Drug Administration’s 23-year-old approval of mifepristone. Essentially, the plaintiffs argue that the FDA acted improperly when it approved this drug in 2000. The case also challenges several subsequent reviews the FDA conducted of the drug, claiming that the agency ignored the evidence that mifepristone was too risky. As a result, the lawsuit asks the court to deem the FDA’s approval of the drug unlawful.

To be clear, mifepristone is one of the most studied drugs in this country. The evidence shows that it is safer than penicillin, Viagra, and thousands of other drugs the FDA has approved. There is no evidence that the FDA acted improperly in approving mifepristone; FDA law scholars and government agencies, like the Government Accountability Office, agree. (If you want to read more about abortion pills, we have a forthcoming law review article available here that explains all you need to know.) So the medical basis for this argument is meritless.

But even if Judge Kacsmaryk does exactly what the plaintiffs are asking of him, regardless of the faulty science, his legal power in this case is limited. First, as an amicus brief from FDA law scholars (including one of the authors of this piece) makes clear, Congress crafted procedures by statute for the FDA to use to withdraw approval of a drug. Judge Kacsmaryk cannot force the FDA to adopt another process to do the same—doing so would violate federal law. At best, he should only be able to order the agency to start the congressionally mandated process, which involves public hearings and new agency deliberations. This could take months or years, with no guarantee of the result.

Second, even if Judge Kacsmaryk forgoes this process and rules that the FDA’s approval was unlawful and that mifepristone is now deemed a drug without approval, he cannot force the FDA to enforce the decision. Because the FDA does not have the capacity to enforce its statute against every nonapproved product on the market, it has long been settled law, decided in a unanimous 1985 Supreme Court decision, that the agency has broad enforcement discretion, meaning the agency, not courts, gets to decide if and when to enforce the statute. The FDA has historically used a risk-based approach to prioritize its enforcement actions, focusing on the products with demonstrated safety concerns. Occasionally, the FDA will issue a guidance document giving some drug manufacturers safe harbor to violate the relevant statute in certain contexts, such as when the safety risk is low, which it has done with products as wide-ranging as infant formula and fecal transplants. It should decide to take a similar approach with mifepristone if the drug’s approval is removed, given the drug’s exemplary safety profile.

Thus, even if Judge Kacsmaryk rules against the FDA, the manufacturers and distributors of mifepristone could, if the FDA chooses not to enforce its restrictions, continue to sell their product and would not have to remove it from the market. They would likely only feel comfortable doing so if the FDA issued guidance protecting them, but offering such guidance would be consistent with past agency policy.

Third, Judge Kacsmaryk’s order, no matter what it says, will only apply to the parties in the case. The FDA is one of the parties that would be bound by the order. The other is Danco, the brand-name manufacturer of mifepristone, which intervened in the case and is now also a party. But no other person or entity would be bound by what he orders, even if Judge Kacsmaryk tries something extreme, like ordering all distributors of mifepristone to cease distribution and all medical care providers to stop prescribing for patients. Doing so would violate basic federal rules of civil procedure as well as constitutional guarantees of due process that require someone to have notice and an opportunity to be heard before a court binds them with a ruling. Thus, neither GenBioPro, the generic manufacturer of mifepristone, nor abortion providers around the country who prescribe mifepristone would be bound by anything Judge Kacsmaryk orders. (Though, to be clear, this is not direct legal advice for any person or entity; everyone needs to consult their own attorney to assess their own risks in this new legal environment.)

The same is true of any rulings on the law that Judge Kacsmaryk makes beyond his orders directed at the parties to the case. One of the claims in the case is that allowing mifepristone to be distributed by mail violates the Comstock Act, an 1873 law—a law that hasn’t been enforced for almost a century—that prohibits mailing anything that can cause an abortion. The Department of Justice has recently said this law has very limited effect because courts narrowed its meaning in the 1930s. Plaintiffs, however, have asked Judge Kacsmaryk to apply the law much more broadly.

If that happens, contrary to precedent and an almost century-long understanding of the law, any ruling he issues about mail would bind the FDA and Danco only. To everyone else, he is just one judge in one trial court. No one beyond the parties has to follow what he says about this archaic statute. Now, if and when Judge Kacsmaryk’s ruling gets appealed, appeals courts’ decisions on the law will have greater import. However, even their orders still bind only the parties to the case and should not limit the FDA’s enforcement discretion.

Judge Kacsmaryk is not all-powerful. There’s a huge amount of authority that the FDA will retain, and we should look to the agency to respond to the judge’s ruling in a way that does not interrupt mifepristone distribution.

And we should also be careful and measured when we talk about this case. It is true that the case is outlandish, and worthy of our attention. But we can anticipate an anti-abortion ruling and prepare for the possible changes in medical care while simultaneously explaining that strong legal arguments grounded in court procedure and FDA law limit the court’s authority. Most importantly, we need to be clear that, no matter what the judge rules, there are scenarios where mifepristone distribution can very likely continue, the same as before, and people who support abortion rights should work to bring those to fruition.