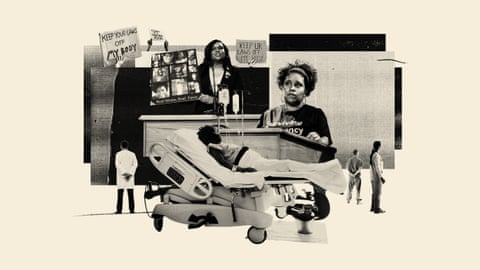

When Nakeenya Wilson learned she was pregnant with her third child, she felt fear, not joy.

The Texas mother had nearly lost her life while giving birth to her son in 2016, leaving her with deep anxiety over her pregnancy the following year. Her unborn child became stuck in her pelvis, a complication known as shoulder dystocia. Medical staff straddled Wilson and manually pushed on her stomach, a painful procedure. He emerged blue, limp and not breathing, recalls an emotional Wilson.

The situation grew increasingly dire as she began to hemorrhage, almost bleeding to death. From the outset of her hospital visit she says she received poor care from nursing staff, who were uncommunicative, delayed a scheduled induction and kept forgetting her name. Without first informing her, a nurse gave Wilson a drug to halt the excessive bleeding, leading to a spike in blood pressure that had already been elevated during her pregnancy due to pre-eclampsia, placing her at risk for seizure.

“I was scared I was going to die,” says Wilson. “I felt ignored and like my pain and my requests for treatment weren’t being taken seriously. It was an incredibly traumatic experience.”

Eventually, the bleeding ceased and Wilson’s son recovered. She went home emotionally scarred and reconsidering plans to further expand her family.

Wilson’s story is emblematic of the risk pregnant patients, particularly Black women, face in the US. The country holds the highest maternal death rate among similarly industrialized countries and is the only developed nation where these deaths are increasing. In 2021, those deaths surged to their highest levels in nearly 60 years, according to new data from the the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In Texas, where Wilson is from, the maternal mortality rate has historically hovered above or close to the US average over the years, about 20.2 deaths per 100,000 live births before the pandemic. Black women are disproportionately affected both nationally and in Texas, according to the latest data, from 2019. And these disparities persist even when accounting for class: the effects of structural racism on Black mothers overpower socioeconomic factors like household income, so the wealthiest Black women and their newborns will still experience worse outcomes than those from the lowest-income white families, according to a recent California-based study.

Maternal health experts argue that expanding Medicaid coverage for mothers to a full year postpartum would significantly alleviate the glaring crisis in Texas, but state lawmakers fell short of doing so during their last legislative session in 2021. While no one is currently being moved off Medicaid due to the pandemic public health emergency, that could change by 1 April, when states will be re-evaluating eligibility, adding renewed urgency for lawmakers to act before nearly 3 million Texans – mostly young adults, children and new moms – lose coverage.

Wilson, a maternal health community advocate, now sits on the state’s Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee, which studies pregnancy-related deaths and offers recommendations to the state.

In December, after a controversial delay, the state finally released the latest data, from 2019, on maternal mortality in the state. The findings revealed Black communities continue to face the worst pregnancy outcomes in the state: Black women are twice as likely as white women and four times as likely as Hispanic women to die from pregnancy and childbirth – inequalities that have persisted for a decade. Obstetric hemorrhage – the leading cause of maternal death in Texas and the complication that nearly killed Wilson – declined overall in recent years, but Black women experienced an increase of nearly 10%, comprising a quarter of overall cases.

“When rates are improving for all other populations but getting even worse for Black women, we need to really acknowledge there is a major disconnect in care,” says Wilson.

Maternal health advocates hope that state lawmakers seize on attention to the report to help alleviate the problem during the current legislative session, which ends in May. The need to take action has never been greater, they say, as the state’s complete abortion ban, in effect following the US supreme court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade, places the lives of those who experience complicated pregnancies at high levels of risk.

Preventative deaths

For years, Texas has only offered Medicaid coverage for 60 days postpartum, while nearly 30 states have sought to expand their coverage to one year, an option made easier by a provision in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

Texas is home to the highest number of uninsured residents in the US as well as the highest percentage of uninsured women of childbearing age. It is one of only 11 states that have declined federal incentives to expand Medicaid across the board under the Affordable Care Act.

Expanding coverage would have a larger impact on women of color: nearly two-thirds of Black women are on Medicaid when they give birth, compared with less than a third of white women.

In perhaps one of the most striking findings, and in line with previous years’ data, the latest Texas report showed 90% of maternal deaths in the state in 2019 were probably preventable.

For years, the review committee’s top recommendation has been to extend Medicaid coverage to new mothers from two months to 12 months, as about one-third of deaths in the state occurred between 43 days to a year postpartum. Continuous healthcare coverage is essential to reducing morbidity and mortality risks, the recent report found.

Yet after the Texas house passed a measure in 2021 to expand Medicaid to one year postpartum, the more conservative Texas Senate sliced that proposal to just six months.

The six-month extension has yet to go into effect as the federal government failed to approve the piecemeal effort, reportedly because of language in the bill that could be interpreted to exclude women who have had abortions. It is still under review by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service.

As she has in the past four legislative sessions, the Democratic house representative Shawn Thierry is working to mitigate the crisis by filing a package of maternal health bills, among them a fresh proposal to extend Medicaid to 12 months postpartum that addresses the federal government’s reported concerns. While the leadership of the Texas house expressed support for an extension, it remains to be seen how the ultra-conservative senate will act.

For the first time, the committee that released the recent Texas data factored discrimination into maternal mortality rates, finding it contributed to 12% of deaths.

Wilson – who considers the figure probably the “tip of the iceberg” in the overall picture – says that the state should make efforts to combat systemic racism in hospital settings, which can often lead to undertreating pain management for people of color.

“I had a terrible experience with this nurse, but she is indicative of a wider, institutional problem,” says Wilson. “We need to start looking at the healthcare system’s biases – either implicit or explicit … or we are never going to see improvement for Black women.”

As a Black mother, Thierry is driven by her own near-death experience giving birth in 2012. During an emergency C-section she was administered an epidural too high in her spine, nearly paralyzing her. Thierry wailed in pain but medical staff dismissed her calls until she begged for anesthesia. The lawmaker, a successful attorney with private health insurance, says she almost died at the hands of medical staff.

“I wasn’t heard, I wasn’t respected and I could have died,” says Thierry. “It’s my duty now to help make sure other women don’t experience what I went through.”

Thierry has also proposed measures to require healthcare providers and medical students to be trained in cultural competency and implicit biases; study why major disparities exist specifically for pregnant Black women; and speed up access to state data on maternal death, which faces a significant backlog – as evidenced by the fact that the report recently released by the state analyzes information from four years ago.

‘The situation is dire’

Months before Roe fell, ushering in a full abortion ban, Texans were living under a six-week ban considered at the time to be the most restrictive abortion law in the US. Texas abortion laws now carry no exception for rape, incest or lethal fetal abnormality. Today, performing an abortion in Texas is a felony punishable by up to life in prison. The laws, say health experts, have added major barriers to not only elective abortion, but life-saving medical intervention during planned pregnancies.

Despite the law’s narrow exception for the life of the patient, doctors and hospitals – facing steep criminal and civil penalties – are often erring on the side of caution. Doctors are turning away patients or delaying abortion care until life-threatening conditions arise, including infection, sepsis, excessive bleeding and even death, found a study in the New England Journal of Medicine. A handful of other nightmarish stories out of Texas – including that of an Austin woman who came close to death in an ICU after contracting a bacterial infection – highlight the harsh reality denying abortion care for medically complicated pregnancies.

Texas officials have yet to clarify when the state’s abortion bans allow for emergency intervention, perpetuating confusion and fear among the medical community. In fact, the state sued the Biden administration to block national guidance that ensures doctors who provide emergency abortion care are protected by federal law. A recently filed Texas lawsuit seeks to clarify those medical exceptions.

There is palpable anxiety among advocates and the medical community that this picture will cause maternal mortality rates to rise.

“The situation here is very dire and extreme. We are already hearing a lot of haunting and traumatic stories,” says Dr Bhavik Kumar, a member of Physicians for Reproductive Health. “We know that when places have restricted abortion access, they also have extremely high maternal mortality rates.”

Indeed, the maternal death rate was 62% higher in states that had abortion bans or serious restrictions on access compared to states with stronger abortion access, according to a 2020 study from the Commonwealth Fund. And a report released in January from the Gender Equity Policy Institute found that women in states with abortion bans are nearly three times as likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth or soon after giving birth.

Researchers stress that state lawmakers who impose abortion bans also often fail to comparatively invest in maternal and reproductive healthcare access, with one report noting that less than a third of abortion-restrictive states have opted to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage for up to one year.

Momentum is growing – even in conservative-led states – to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage. Thierry hopes this legislative session her Republican colleagues prove they vote consistent with their ostensible pro-life values.

“If you are pro-life then you have to be pro-maternal care,” says Thierry. “We have to care as much about ‘unborn children’ as we do born children and their mothers. There is no in between, otherwise it’s just hypocrisy.”