In the fall of 2017, I sat in a windowless back room in O’Neill’s bar in the Maspeth neighborhood of Queens and watched the Retired Detectives of New York (RDNY) honor two of their own.

The first was Louis Scarcella, whose record of high-profile arrests in Brooklyn in the 1990s had just crumbled under evidence that he’d coerced people into giving false confessions. The second was John Russo, who’d only recently become tabloid famous: He’d identified a Black man as a suspect in the murder of Karina Vetrano, a 30-year-old white woman who was killed in the summer of 2016 while jogging near her family’s home in Queens.

I was covering the event for New York magazine. Russo’s police work was a “true iteration of that cinematic ‘detective’s intuition’ that cops love to valorize,” I wrote. “It’s the same one Scarcella was so famous for before the allegations appeared to suggest he was just making all that shit up.”

The name of the man Russo ID’d is Chanel (pronounced “Tcha-nel”) Lewis. At Lewis’s trial Russo testified that on Memorial Day, about two months before Vetrano’s murder, he was off-duty and in his car with his daughters when he saw Lewis, then 19, walking through the majority-white neighborhood of Howard Beach. Russo deemed him suspicious and tailed him for 45 minutes. When Russo spotted him while off-duty the next day too, he alerted nearby police. The officers stopped Lewis and drove him to a McDonald’s in the Far Rockaway neighborhood of Queens, where he was questioned.

In Russo’s telling, seven months after Vetrano’s murder, he suddenly remembered Lewis and established him as a person of interest. When police officers went to his house, Lewis voluntarily gave them a DNA sample that matched DNA found on Vetrano’s neck, on her phone, and on her fingernails. Lewis was arrested on February 4, 2017, and he confessed to killing Vetrano the next morning. Russo’s story was that he had a hunch, and it hit.

That night in Maspeth, Russo was low-key while his fellow cops swooned. “Because of his actions an animal was put behind bars,” an RDNY organizer said. They presented Russo with the ARDY, “our highest honor.” As the ovation died down, Russo took the podium and addressed Vetrano’s family, who was seated nearby. “We all work together every day to bring justice to every crime victim’s family; we thank them for being here. God bless this police department. God bless the people of the city of New York.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In Lewis’s first trial, in 2018, the jury couldn’t reach a verdict and the judge declared a mistrial. During his second trial, in 2019, an anonymous whistleblower who self-identified as a member of the New York Police Department sent a letter to Lewis’s attorneys stating that Russo’s story was a fabrication. For nearly two weeks after the murder, according to the whistleblower, the cops assigned to the case were told to look for “two jacked up white guys.” Then, the whistleblower alleged, the NYPD’s Forensic Investigations Division received a report stating that the DNA found at the crime scene belonged to a Black man. In the following months, the whistleblower said, the NYPD stopped hundreds of Black men in Howard Beach and its surrounding area and swabbed them for DNA evidence.

The letter included a copy of a partial record of the men whose saliva was tested that had come from an internal NYPD database, something only an officer with knowledge of the case would have access to. The New York Times confirmed that the DNA collection had taken place, and the Daily News interviewed some of the men, who described a pattern of intimidation that they and their families endured while the NYPD aggressively sought out swabs. In one case, a family sold their house and moved to Westchester County to get away from police harassment. The Queens County District Attorney’s Office has never denied the authenticity of the whistleblower’s letter; it has just ignored its claims.

After receiving the letter, Lewis’s then-lawyers, who were working on behalf of the Legal Aid Society, moved to reopen pretrial proceedings for more discovery. They wanted to learn how the NYPD had come to identify their client as a suspect. The judge rejected that motion, and Lewis was convicted by the jury. Since 2019, he has been serving a sentence of life without parole in various New York State prisons.

Lewis, now 26, is represented by the veteran defense attorneys Rhiya Trivedi and Ron Kuby. They believe that Lewis was just another name on the NYPD’s list of Black men who’d been previously arrested or detained in or around Howard Beach and that the department used John Russo’s hunch story to cover up its tactics in the Vetrano investigation—an indication, Trivedi said, of “what the NYPD does when they are truly desperate,” of “how far they’re willing to go.”

If they’re right, the Queens DA would be guilty of a Brady violation, meaning a failure by the prosecution to provide the defense with exculpatory evidence. If the DNA match and confession in the Vetrano investigation came from a search tactic that was never disclosed in court, that evidence could be ruled inadmissible, and Lewis’s conviction could be overturned.

After researching Lewis’s case, Kuby and Trivedi guessed that Parabon NanoLabs was the company that provided the NYPD with the DNA report cited in the whistleblower’s letter. The private lab, funded in part by the Defense Department and headquartered in Reston, Va., is one of the few places in the United States that analyzes DNA from police investigations to determine a person’s race.

The Queens DA never mentioned Parabon during Lewis’s two trials. And while the company touts its successes in police investigations—its website boasts of work in 33 states, plus Canada and Sweden—Parabon had never discussed its role in the Vetrano murder case.

Recently, I spoke by phone with Parabon’s director of bioinformatics, Dr. Ellen Greytak. She’d agreed to speak about the company’s work with police departments. Fifteen minutes into our conversation, I asked about the Vetrano investigation.

“We did ancestry for that case,” Greytak said, then added that from the sample they were given, they felt confident to say the individual was “of African and European descent.”

I asked for clarification. Does that mean the report suggested the person could have been either of African or European descent?

“The report says ‘African,’” Greytak said. “I think the focus was mostly of African…” She trailed off. “Most people of African descent are also of European descent. I’m trying to remember. I remember he was of African descent. So that’s the extent of it. I don’t know if we also said ‘and European.’”

I asked her to share the report with me. She offered a terse rejection. “Whatever the police said is what we’re allowed to say.”

In 2017, the New York State Department of Health issued a warning to Parabon for operating in New York without a permit, stating that this was a misdemeanor “punishable by fine or imprisonment or both.” The department took this action after it became aware that the NYPD had sent Parabon specimens from two separate 2017 Brooklyn murder cases. In an e-mail exchange, Thom Shaw, a case manager at Parabon, confirmed that it was the NYPD’s Forensic Investigations Division that had hired Parabon in 2016 for DNA analysis during the Vetrano investigation.

It wasn’t until 2020 that the Department of Health approved Parabon’s application for a permit. I asked Greytak why the company had worked with the NYPD before it was allowed to do so. “We were told that they were outside the permitting process and that they could make their own decision based on what labs they sent things to,” Greytak said. “We trusted them on that.”

Parabon’s confirmation of the existence of a report indicates that, as Trivedi and Kuby contend and as the whistleblower alleges, the NYPD covered up its tactics in the Vetrano investigation and that the Queens DA protected the flawed prosecution of Lewis by burying the NYPD’s illegal use of a private lab.

What’s in Parabon’s report? How exactly did it lead to the NYPD’s arrest of Lewis? And why won’t the department disclose any of that information?

The NYPD did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

There is, of course, another question: Is Chanel Lewis innocent? But for now, Kuby and Trivedi don’t need to prove that. What they need to show to overturn his conviction is that Lewis was wrongfully convicted. And if they do, we’ll learn something about how law enforcement functions in New York City.

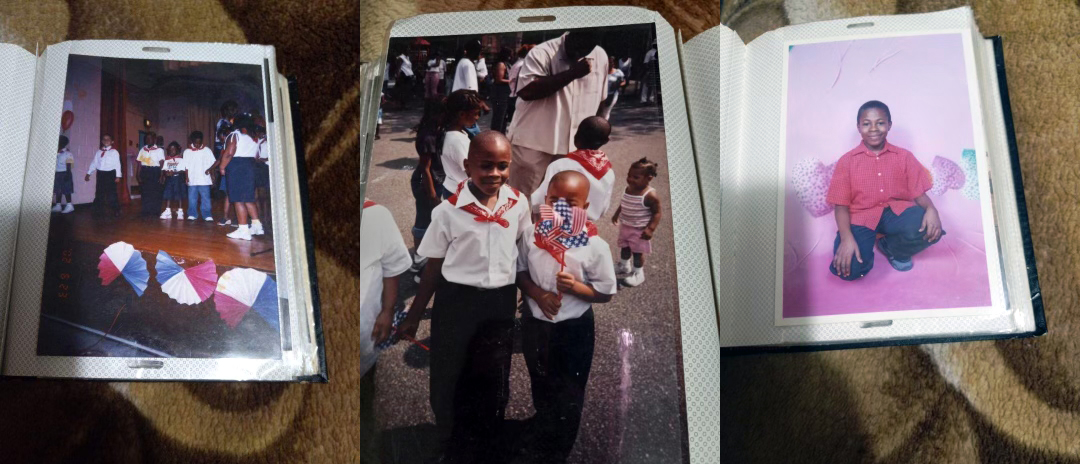

Chanel’s mother, Veta, had moved to New York from St. Mary Parish, in northeastern Jamaica, in the early ’90s. One Friday in the winter of 2017, two plainclothes officers, a man and a woman, came to her front door. She told me this was her first-ever interaction with the NYPD.

They said to Veta, “We need to talk to Chanel.” She said, “Pertaining to what?” The woman asked Veta if she had “heard about this lady in Howard Beach.” Veta said she knew about the murder of Vetrano. The female officer told her something to the effect that “no one person could ever have killed Karina Vetrano.” Meanwhile, the male officer pulled Chanel aside. Veta didn’t know that the officers didn’t have a warrant, which meant Chanel could refuse the request for a DNA sample. She didn’t even know they were taking a DNA sample.

The next day, Veta, a home nursing aide, woke up at 4 am to go to one of her two jobs. While she was gone, the police arrested Chanel. “When I came home, I couldn’t even get inside,” Veta told me. The NYPD was swarming her residence. “I dropped down right outside. I collapsed.”

When she asked which precinct Chanel had been taken to, she said the cops claimed they couldn’t provide that information. “He did not come home. He did not come home, and until now he’s still not home,” she said.

On Sunday morning, Veta watched the local news and waited for information from the police. There was a breaking news bulletin. “I saw his face on the TV, and I hear someone say, ‘They have a confession. They have a confession.’”

Before his arrest, Lewis, a recent graduate from a high school for developmentally delayed students, had never spent a night away from home. Police held him for 11 hours, overnight. The morning after his arrest, Detective Barry Brown secured Lewis’s confession.

In the video of the confession, Lewis comes off confused, tentative, and afraid. The confession is coached out of him, painfully, bit by bit. A Queens assistant DA repeatedly offers a statement about Lewis’s actions during his alleged attack on Vetrano in Howard Beach and then cajoles Lewis into confirming it. At one point, the assistant DA prompts Lewis to explain that the reason he attacked Vetrano was that he was upset about loud music that an unidentified person had been playing in his East New York neighborhood earlier that day.

Despite the coaching, Lewis gets details wrong. Most glaringly, he says that Vetrano died by asphyxiation with her face in a puddle, which did not happen. At the end of the confession, he appears to believe that the assistant DA taking his statement is his own defense lawyer and fumblingly asks about a “restitution” program that he indicates was offered before the recording began.

Barry Brown recently resigned from the NYPD after he was caught hiding exonerating evidence in a different murder case, leading to a $2 million settlement.

Ron Kuby, 66, has been a pugnacious civil rights attorney for decades. His office in the Flatiron District of Manhattan is in a converted factory loft with futons, hammocks, and at least one mural of an octopus. When I visited him in the spring, he looked on-brand in a colorful tie and a long white ponytail. Trivedi, 32, started working with Kuby right out of law school about five years ago. In her boots and black cut-off T-shirt, she looked like a singer in a critically acclaimed but obscure industrial metal band. The first thing Trivedi said to me was “Do you like dogs?” Then Jack and Sammy trotted up. By the time we finished our interview, Kuby was in his socks tucking into a massive burrito.

At the time of Lewis’s trials, Trivedi and Kuby were defending a young Queens man named Prakash Churaman, who had been arrested on a felony murder charge at 15 and sentenced to nine years to life in prison. Churaman had long maintained he’d been coerced into confessing to Barry Brown. Trivedi and Kuby succeeded in overturning Churaman’s conviction, in part by focusing on the judge’s denial of Churaman’s request to call an expert witness on false confessions.

After their success with the Churaman case, Trivedi and Kuby were hired to work on Lewis’s appeal by a person who wished to stay anonymous. “Some nice Italian American citizen from Queens called me up,” Kuby said. “And he really does not want his name known, because he lives in that community,” meaning Howard Beach. The amount this person could pay was low, but, Trivedi says, she and Kuby were “hyped” to take on the case.

As their first action, Trivedi and Kuby sent a letter to the Queens DA asking for documents and communications from the Vetrano investigation. Any police work that occurs during an NYPD investigation is recorded in a report called a DD-5. Trivedi said she’d never seen a case with more than 100 DD-5s. The Vetrano investigation had 1,786, and only 129 were made available. The DA rejected Kuby and Trivedi’s requests. “They told us to go fuck ourselves,” Trivedi said.

The forensic practice by which race is inferred from DNA is called “phenotyping,” and it’s a relatively new and scientifically contested method. Parabon’s Greytak said that the company’s report from the Vetrano investigation indicated that the DNA sample belonged to a man of African descent. (As she let slip in our conversation, the report may also have described the sample as being from someone of European ancestry.) The NYPD clearly took that to mean they were looking for a Black man. But Trivedi argues that racial definitions are not as clear-cut as the NYPD wants them to be, and that the whole premise of phenotyping as an investigatory tool is flawed.

“What does it mean for DNA to be Black?” she asked. “Who’s making that determination? And is the NYPD just free to stop anyone [Black] at that point?”

Bradley Malin, an expert in genetics privacy at Vanderbilt University, told me that knowing the likely “ancestral heritage” of a given DNA sample doesn’t necessarily indicate what the person whose DNA it is looks like. “There are plenty of reasons why skin tone could be a lot lighter or could be a lot darker,” he said, and “there have been plenty of [cognitive] studies that indicate if you just show an individual skin tone and you ask, ‘Are they Black or are they white?,’ people get it wrong.”

Parabon has not submitted its technology to peer review and treats its DNA tools as trade secrets. “If this is going to be technology that is used to prosecute individuals,” Malin said, “then it would be useful to have public scrutiny into whether the approach is reliable.”

As far as Trivedi knows, the one time prosecutors attempted to enter Parabon’s phenotyping as evidence was in the infamous murder trial of Navy SEAL Eddie Gallagher, and the judge threw it out. Trivedi argues that the use of Parabon in the Vetrano investigation should be “exculpatory or at the minimum subject to cross-examination.” She’s writing a motion that will request discovery on the DNA report and attempt to show the judge “what the defense would have done had they had a chance” to challenge the science.

That motion will go to Justice Michael B. Aloise, who presided over both of Lewis’s trials and demonstrated a favorable attitude toward the prosecution’s case by dismissing the defense motion related to the whistleblower letter. If Aloise rejects the motion, Kuby and Trivedi will move forward with an appeal to the Appellate Division, which can order discovery or vacate the conviction altogether.

It’s important to point out one thing: The DNA sample taken from Lewis and then matched to the samples from Vetrano were analyzed not by a secretive, private DNA lab but by the city’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, and the OCME said they matched.

In Lewis’s trial, the defense pointed out that there were only trace amounts of Lewis’s DNA present and that they could have gotten there through secondary transfer, meaning Vetrano could have picked up Lewis’s DNA by touching something Lewis had previously touched. In 2012, a man in California was wrongly incriminated in a murder because of exactly that kind of secondary transfer. Studies have shown that one in five people carry traces of strangers’ DNA.

This theory is bolstered by the fact that, unlike the DNA found on Vetrano’s phone and neck, the DNA found on her fingernails was matched to Lewis’s DNA by something called the Forensic Statistical Tool, a process that has since been proved to be unreliable and that the OCME has stopped using. That would make it possible that Lewis is serving a life sentence because of an everyday, arbitrary transfer of DNA.

The Queens district attorney has always maintained that the DNA match indicated Lewis’s guilt. But if the DA is right, that would lead us to a counterintuitive conclusion: Lewis could be both guilty and wrongfully convicted. Because the fundamental question remains: Was the DNA sample from Lewis that the OCME analyzed illegally procured?

On June 6, Prakash Churaman arrived at the Queens County Courthouse believing he was there to get a trial date. By his supporters’ count, it was his 98th court appearance since his arrest. Veta Lewis was there too, shielded behind a mask and large sunglasses. She’d been to a lot of Churaman’s hearings and rallies. After one event at Queens College, Veta and Churaman’s mother went out for pizza at Gino’s of Kissena. In the eyes of many community activists, Churaman’s and Lewis’s cases are twin symbols of the crimes that the NYPD perpetrates on young people of color in Queens.

Outside the courthouse, one speaker pointed out that “Barry Brown sent another community member, Chanel Lewis, to prison. We are very much in solidarity with Chanel Lewis.” Another added, “Chanel is still incarcerated. The same detective. Isn’t that a shame? It’s a damn shame.”

After Churaman’s conviction was overturned, the Queens DA offered him a deal: plead guilty to a lesser charge and go free within months. Boldly, preposterously, Churaman rejected the agreement and asked for a new trial. He wanted to fight for a full acquittal. (Kuby and Trivedi, who’d advised him to take the deal, stopped representing Churaman at this point.)

It was a broiling afternoon, but the heat didn’t stop Churaman from pulling off an impeccable black-vest-and-tie look. As a news team for the PIX 11 TV station set up, he rounded up a group of supporters to crowd him with homemade “Free Prakash” signs.

As the camera rolled, it became clear that the years since his arrest had made Churaman into a virtuosic defender of his cause. As he talked about his seven years of incarceration and his 16 months under house arrest, he stayed composed. “I was a 15-year-old child that was literally kidnapped by one of the most notorious police departments in this country,” Churaman said. “I witnessed and experienced traumatic incidents that I’m still living with.” Nearby, a young man in Reef slides shook the dwindling cubes in his ice coffee and shouted, “Where’s Melinda? She gonna speak on it?”

The Reefs man was referring to Melinda Katz, the Queens district attorney, whose office is in the courthouse. Katz, a career bureaucrat, was elected in November 2019 after repositioning herself in the primary as a criminal justice reformer, defeating the progressive public defender Tiffany Cabán by 60 votes. Once in office, Katz fulfilled a campaign promise to establish a Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU), a department within the DA’s office dedicated to investigating possible wrongful convictions.

For the last decade, CIUs have been popping up around the country, and they can be effective tools for undoing prosecutor misconduct. But as often as not, DAs use CIUs to brand themselves as progressive but then fail to provide them with enough resources to be effective. According to the National Registry of Exonerations’ CIU tracker, 42 units have won a total of 662 exonerations, while another 54 have collectively exonerated no one.

The Queens CIU has overturned seven convictions involving sentences ranging from 15 years to life without parole. A CIU investigation uncovered major malfeasance by Lewis’s prosecutor, Brad Leventhal, forcing him to resign after having tried more than 80 cases during his decades-long career at the DA’s office.

Activists in Queens have requested that Katz send Lewis’s case to the Queens CIU. Generally, CIUs don’t investigate cases like Lewis’s, in which all traditional legal avenues have yet to be exhausted. But there’s no reason a CIU couldn’t look at a case before it’s gone through appeal. And during her campaign, Katz promised to review the Lewis case.

Ultimately, Katz opted to examine the case internally, without any of the transparency of a CIU process.

In a statement, Katz said, &8220;I have assessed the proof at trial, called for renewed examination of thousands of pages of documents, and consulted experts when reviewing the forensic evidence. Further, I asked my Conviction Integrity Unit to review the most critical evidence—DNA evidence which incriminates the defendant in the murder of Ms. Vetrano. As a result of this painstaking process, I am confident that the evidence supports the jury’s verdict.”

No details of the review were shared publicly. But Katz’s use of the CIU to look at the Lewis case raises questions: How often does the Queens DA enlist the CIU to informally review cases outside of the stated CIU protocols? Can the CIU be an independent entity, or is it subordinate to the DA?

Back at the rally for Churaman, a stream of supporters—from bike radicals to buttoned-up politicians—took turns jogging up the courthouse steps. “I want to express my gratitude to Prakash for having so much dignity in the face of so much bullshit,” one said. Nearby, Churaman’s mother and girlfriend tended to his infant child. Young men who could have been his cousins or the kids he grew up with crowded the stairs.

It was time for Churaman to head into court. For his previous hearing, he said he could bring only eight people, but this time anyone could enter. It was the first inkling that something might be up. Inside the dark wood courtroom, as all the parties shuffled into place, Churaman’s lawyer clapped him on the shoulder and whispered in his ear. Churaman let out a shout, bolted to the back of the room, crouched, and rocked on his heels.

The rest of the process was routine. The assistant DA read out a statement: “The people continue to maintain defendant’s guilt…. Due to defendant’s age now, prosecution in Family Court is no longer an option. As a result, the counts must be dismissed.” The DA was responding to a motion Churaman’s lawyer had filed at his behest raising an “infancy defense.” Because Churaman was a teen when the crime occurred, he should be tried in Family Court. But because he was now an adult, he could no longer be tried in Family Court. What the Queens DA was saying, in effect, was that it had no way to try the case. The judge mumbled through the rest, and then it was over.

It was hard to understand in the moment, but all the charges had just been dropped. Churaman’s wild bet had paid off. He didn’t need to plea-bargain. He wouldn’t be forced to admit guilt. He wasn’t going back to prison. He wasn’t even going back to trial. “Free!” someone screamed into a cell phone. “Completely fucking free!” There were whoops in the hallway as supporters crowded around him. Veta Lewis followed him closely. “Never had no case,” she said. Another supporter shouted, “Chanel’s next, yo. Chanel’s next!”

On the street, Churaman embraced his lawyer and cried. A woman with white hair put her fists in the air and shouted “Whooo!” as if the Knicks had just made the playoffs. Churaman’s primary concern was getting the ankle bracelet monitor cut off. “I’m about to call the sheriff, bro!” he announced. He rolled up his pant leg to reveal the ankle monitor and a sock reading “Good Vibes.”

The PIX 11 camera came back, and a woman in an apron showed up with tiny plastic cups and a bottle of champagne that she handed to Churaman. He grinned and said, “I don’t even know how to pop a bottle!” The phones were filming; little cups were in the air. A few hours after the hearing, Churaman headed to the sheriff’s office, where they did, eventually, cut off that monitor.

For all their apparent similarities, Churaman’s and Lewis’s cases differ widely in their context. Churaman was accused not of committing a murder but of being an accomplice to one. And the victim, Taquane Clark, was a young Black man whose death never received the kind of tabloid attention that Vetrano’s did.

And even if Lewis were to get out on house arrest, he would never be able to fashion himself into a telegenic self-humanizer like Churaman. There are details I could add now, to make you feel like you know Lewis better. Like how he wanted to be a pilot when he was a kid and how he’d have food ready for his mother when she came home from work. But it shouldn’t matter what kind of person Chanel is or what kind of victim Vetrano was. What should matter is whether Lewis was wrongfully convicted. What should matter is that the NYPD used Parabon and that the Queens DA never admitted it.

It’s crucial to remember that, right now, innocence or guilt isn’t the question. Because of the tactics of the NYPD and the Queens DA, this has become a case about how policing and the criminal courts really work in New York City.

“Can you use Parabon in a criminal case?” Trivedi asked. “Keep it from the defense? Never subject it to the light of day? And let a guy do life without parole?”

For now, at least, the answer is yes.